PURE WICKEDNESS!!!

AP Documents Land Taken From Blacks Through Trickery, Violence and Murder

By TODD LEWAN and DOLORES BARCLAY

Associated Press Writers

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

For generations, black families passed down the tales in uneasy whispers: ''They stole our land.'' These were family secrets shared after the children fell asleep, after neighbors turned down the lamps - old stories locked in fear and shame.

Some of those whispered bits of oral history, it turns out, are true.

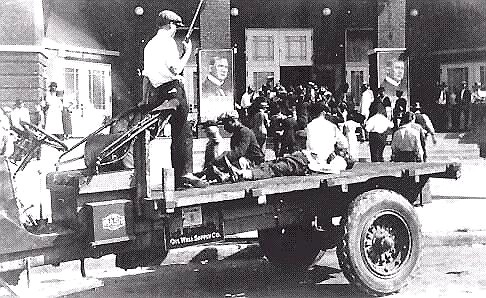

In an 18-month investigation, The Associated Press documented a pattern in which black Americans were cheated out of their land or driven from it through intimidation, violence and even murder.

In some cases, government officials approved the land takings; in others, they took part in them. The earliest occurred before the Civil War; others are being litigated today.

Some of the land taken from black families has become a country club in Virginia, oil fields in Mississippi, a major-league baseball spring training facility in Florida.

The United States has a long history of bitter, often violent land disputes, from claim jumping in the gold fields to range wars in the old West to broken treaties with American Indians. Poor white landowners, too, were sometimes treated unfairly, pressured to sell out at rock-bottom prices by railroads and lumber and mining companies.

The fate of black landowners has been an overlooked part of this story.

The AP - in an investigation that included interviews with more than 1,000 people and the examination of tens of thousands of public records in county courthouses and state and federal archives - documented 107 land takings in 13 Southern and border states.

In those cases alone, 406 black landowners lost more than 24,000 acres of farm and timber land plus 85 smaller properties, including stores and city lots.

Today, virtually all of this property, valued at tens of millions of dollars, is owned by whites or by corporations.

Properties taken from blacks were often small - a 40-acre farm, a general store, a modest house. But the losses were devastating to families struggling to overcome the legacy of slavery. In the agrarian South, land ownership was the ladder to respect and prosperity - the means to building economic security and passing wealth on to the next generation. When black families lost their land, they lost all of this.

Besides the 107 cases the AP documented, reporters found evidence of scores of other land takings that could not be fully verified because of gaps or inconsistencies in the public record. Thousands of additional reports of land takings from black families remain uninvestigated.

Two thousand have been collected in recent years by the Penn Center on St. Helena Island, S.C., an educational institution established for freed slaves during the Civil War. The Land Loss Prevention Project, a group of lawyers in Durham, N.C., who represent blacks in land disputes, said it receives new reports daily. And Heather Gray of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in Atlanta said her organization has ''file cabinets full of complaints.''

AP's findings ''are just the tip of one of the biggest crimes of this country's history,'' said Ray Winbush, director of Fisk University's Institute of Race Relations.

Some examples of land takings documented by the AP:

•After midnight on Oct. 4, 1908, 50 hooded white men surrounded the home of a black farmer in Hickman, Ky., and ordered him to come out for a whipping. When David Walker refused and shot at them instead, the mob poured coal oil on his house and set it afire, according to contemporary newspaper accounts. Pleading for mercy, Walker ran out the front door, followed by four screaming children and his wife, carrying a baby in her arms. The mob shot them all, wounding three children and killing the others. Walker's oldest son never escaped the burning house. No one was ever charged with the killings, and the surviving children were deprived of the farm their father died defending. Land records show that Walker's 2 1/2-acre farm was simply folded into the property of a white neighbor. The neighbor soon sold it to another man, whose daughter owns the undeveloped land today.

• In the 1950s and 1960s, a Chevrolet dealer in Holmes County, Miss., acquired hundreds of acres from black farmers by foreclosing on small loans for farm equipment and pickup trucks. Norman Weathersby, then the only dealer in the area, required the farmers to put up their land as security for the loans, county residents who dealt with him said. And the equipment he sold them, they said, often broke down shortly thereafter. Weathersby's friend, William E. Strider, ran the local Farmers Home Administration - the credit lifeline for many Southern farmers. Area residents, including Erma Russell, 81, said Strider, now dead, was often slow in releasing farm operating loans to blacks. When cash-poor farmers missed payments owed to Weathersby, he took their land. The AP documented eight cases in which Weathersby acquired black-owned farms this way. When he died in 1973, he left more than 700 acres of this land to his family, according to estate papers, deeds and court records.

• In 1964, the state of Alabama sued Lemon Williams and Lawrence Hudson, claiming the cousins had no right to two 40-acre farms their family had worked in Sweet Water, Ala., for nearly a century. The land, officials contended, belonged to the state. Circuit Judge Emmett F. Hildreth urged the state to drop its suit, declaring it would result in ''a severe injustice.'' But when the state refused, saying it wanted income from timber on the land, the judge ruled against the family. Today, the land lies empty; the state recently opened some of it to logging. The state's internal memos and letters on the case are peppered with references to the family's race.

In the same courthouse where the case was heard, the AP located deeds and tax records documenting that the family had owned the land since an ancestor bought the property on Jan. 3, 1874. Surviving records also show the family paid property taxes on the farms from the mid-1950s until the land was taken.

AP reporters tracked the land cases by reviewing deeds, mortgages, tax records, estate papers, court proceedings, surveyor maps, oil and gas leases, marriage records, census listings, birth records, death certificates and Freedmen's Bureau archives. Additional documents, including FBI files and Farmers Home Administration records, were obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

The AP interviewed black families that lost land, as well as lawyers, title searchers, historians, appraisers, genealogists, surveyors, land activists, and local, state and federal officials.

The AP also talked to current owners of the land, nearly all of whom acquired the properties years after the land takings occurred. Most said they knew little about the history of their land. When told about it, most expressed regret.

Weathersby's son, John, 62, who now runs the dealership in Indianola, Miss., said he had little direct knowledge about his father's business affairs. However, he said he was sure his father never would have sold defective vehicles and that he always treated people fairly.

Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman examined the state's files on the Sweet Water case after an inquiry from the AP. He said he found them ''disturbing'' and has asked the state attorney general to review the matter.

''What I have asked the attorney general to do,'' he said, ''is look not only at the letter of the law but at what is fair and right.''

The land takings are part of a larger picture - a 91-year decline in black landownership in America.

In 1910, black Americans owned more farmland than at any time before or since - at least 15 million acres. Nearly all of it was in the South, largely in Mississippi, Alabama and the Carolinas, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. Today, blacks own only 1.1 million of the country's more than 1 billion acres of arable land. They are part owners of another 1.07 million acres.

The number of white farmers has declined over the last century, too, as economic trends have concentrated land in fewer, often corporate, hands. However, black ownership has declined 2 1/2 times faster than white ownership, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission noted in a 1982 report, the last comprehensive federal study on the trend.

The decline in black landownership had a number of causes, including the discriminatory lending practices of the Farmers Home Administration and the migration of blacks from the rural South to industrial centers in the North and West.