I do think losing and being ko'd does hurt your legacy. We look at everything. Doesnt mean great fighters that were ko'd arent still considered great but lets say if Manny never got ko'd and never lost he would be considered way higher than he is now. Just like if Floyd loses or gets ko'd it will tarnish his untouchable rep. The good thing about Floyd is the longer he goes he is approaching ages where most fighters are considered past their prime so if he loses some will just say awe he was past his prime so it may not hurt him much if say he lost 5 years ago at like age 32. Everything is considered and it all counts toward ones legacy good or bad. Got Em!!

Boxing News Thread

- Thread starter heyzel

- Start date

word on the street is non-sense lol We've heard so many times they were negotiating this.

I thought of an idea... Have HBO and Showtime both host the fight. TR can handle everything regarding the HBO promotion but Floyd has to agree to be on 2 24/7 episodes. GB handles everything on the Showtime and gets 2 all access episodes. Then let the fans decide if they order the PPV on Showtime or HBO and split the money that way.

I thought of an idea... Have HBO and Showtime both host the fight. TR can handle everything regarding the HBO promotion but Floyd has to agree to be on 2 24/7 episodes. GB handles everything on the Showtime and gets 2 all access episodes. Then let the fans decide if they order the PPV on Showtime or HBO and split the money that way.

Word on the street is that behind the scene they are working the Mayweather vs. Manny fight. That is why you are seeing the trash talking and both guys have not announced who they fighting.

Won't get happy until contracts are signed.

Won't get happy until contracts are signed.

In his recent interview with the Manila Bulletin, Pacquiao said he has already moved the schedule of his next fight from April to May 3 with the hope of meeting Mayweather on that specific date. Pacquiao said facing Mayweather will surely be intriguing, a fight that would live up to its hype.

"That would be a great fight [with Mayweather], a great match up," Pacquiao added, who just turned 35 Dec. 17.

Props:

CZAR and CZAR

I thought he was willing to push back the dat to May 3 with TR talking to JMM about a fifth rematch with Manny? I know that they were trying to have JJM vs Bradley on the same date as Canelo vs Floyd but Showtime was easily going to win so TR backed out. But with Floyd not having any opponent ppv worthy nor a good undercard TR is willing to put Manny vs JMM 5 on May 3. That would definitely out sell and hurt Showtime like a muthafucka. The fight with Floyd and Manny won't happen cuz that would be TR time to have an undercard like GGG vs Quillin or Garcia vs Provodnikov but the networks won't allow it and GBP will lose those fights. That would be bad ass tho

This happened one time in history. Mike Tyson was Showtime and Lennox Lewis HBO. They had a split HBO/Showtime PPV. Don't see that happening now though (,with the Hershman, Al Haymon/GB fued).

Nytimes Article On Jermain Taylor

SAN ANTONIO — It was about 4 p.m. at a cavernous Alamodome that, in only a few hours, would hold 11,000 screaming boxing fans. But at this moment, in the middle of a Saturday afternoon in December with the sun still shining and the television cameras turned off, Jermain Taylor entered the ring for a bout for the first time in 14 months. If the approximately 200 fans who had filtered into the arena by that point recognized Taylor from his past, they did not act like it.

When Taylor knocked out the journeyman J. C. Candelo in the seventh round of their fight on Dec. 14 the buzz in the arena was nearly nonexistent. Taylor’s was the second fight on a big card, and his bout — a fight, mind you, that in Taylor involved a former undisputed middleweight champion who had twice beaten Bernard Hopkins — was not seen on television.

Taylor won the fight. He celebrated. He left the ring. And almost immediately afterward, the boxing world focused on something else.

This is where Taylor finds himself these days. This is what happens when a 35-year-old — who was knocked out twice in terrifying fashion by world-class super middleweights in a six-month stretch, who sustained a brain bleed that should have made him consider hanging up his boxing gloves forever — makes a comeback against long odds.

He is placed in the second row of the news conference dais, next to the boxers who are just beginning their careers and behind the big stars of the fight card. His quotations from that news conference are not distributed to the news media, because he is not fighting on TV. He becomes nearly as irrelevant as his competition, Candelo, the handpicked opponent that Taylor was fighting.

Why do it, then? Why subject yourself to more head blows, more punches to the face, the indignity of the back row? By all accounts, Taylor does not need the money. Why is he bothering?

“Man, what else am I supposed to do?” Taylor said a few minutes after dispatching Candelo.

A shrug of the shoulders.

“That’s what I’m saying,” he said. “I have nothing else to do. I’ve been doing this job since I was 12. This is my life. When I took those years off, I sat back and thought about it: ‘What am I supposed to do?’ ”

That was not the only question Taylor needed to answer as he began his journey back to relevancy. Taylor, a 2000 Olympic bronze medalist, also had to prove he was healthy enough to resume what had been an impressive career that included holding all four major middleweight belts at the same time.

But by 2009, he was coming off two losses to Kelly Pavlik — including one by knockout — and Taylor moved from the 160-pound middleweight class to the 168-pound super middleweight limit to challenge for Carl Froch’s world title. Although Taylor was ahead on two of the three judges’ scorecards, Froch knocked out Taylor with 14 seconds left in the 12th round. Six months later, Arthur Abraham brutalized Taylor in the final round with one punch that felled Taylor as if he had just stepped off a cliff. Only six seconds remained in that bout when it was stopped.

After the fight, Taylor asked his wife, Erica, and his promoter, Lou DiBella, in what round he had been stopped. He asked again a few minutes later. And again a few minutes after that. That was when Taylor’s team knew something was wrong, and soon after, Taylor, who had a brain bleed and a concussion, temporarily stepped away from the sport. His health, he knew, was at stake.

“I’ve seen a guy who I was with at the Olympics training camp, and he can’t even talk now,” Taylor said. “His brain swelled up, and his speech was slurred. I don’t want to be like that. But he chose his sport. I chose this sport. And I love it.”

It was in part for that reason that he wanted to return to boxing. That and because he does not want his children to see those brutal defeats mark the end of his career.

So he called his former trainer Pat Burns, who was fired during Taylor’s original middleweight title run, to see if they could work together again.

“No, no, no,” Burns said. Taylor flew to Miami to persuade him. Burns wanted Taylor to undergo neurological tests before he would commit to working with him. Taylor said he had been tested in his home state, Arkansas, but Burns still was not convinced the fighter was fit for a return.

Instead, Burns persuaded Taylor to visit the Mayo Clinic. He sent him to the Cleveland Clinic, and the stringent Nevada Athletic Commission. All three cleared Taylor to fight. “We’re ready to go, right?” Burns said an eager Taylor had asked him after the testing was complete. “Nope,” Burns said. “We’re going to take another six months off.”

Burns knows about bad concussions. A Marine, he sustained a head injury during a tour in Vietnam. As he recovered in a hospital for the next year, Burns saw the positive effects rest could have on a head injury. He made sure Taylor would have plenty of rest — 26 months of rest, in fact.

“The thing that’s important is he had two years off,” Burns said. “Unlike the N.F.L., where these guys get knocked out in the first quarter of the game, and if they’re coherent, they come back in the third quarter, the rest did Jermain good. Allow him to rest, he’ll be fine. If you continue to pound the bruised area, you’ll never recover. Whatever the damage was, he had more than enough time to heal.”

More than anything, Burns repeats the same mantra: it took us 24 fights, about four and a half years into Taylor’s career, to be good enough to beat Hopkins for the first time in 2005; It will take us some time now to get back to the championship level.

Taylor’s comeback attempt has not been smooth. He had three convincing wins from December 2011 to October 2012, but he was knocked down by Caleb Truax in a bout that mirrored the ending sequence of the Abraham fight. Taylor got up and won, but a confidence builder it was not.

In May 2012, a woman in Little Rock, Ark., accused Taylor of rape, and though she later recanted her story, the married Taylor admitted to ESPN.com this month that he had a relationship with the woman, whom he called a longtime friend.

But after 14 months out of the ring, his performance against Candelo was the best he has looked in his comeback. Until Taylor faces a truly dangerous opponent, however, nobody — not Taylor and certainly not Burns — knows how he will react.

“Very few boxers get a second chance,” Burns said. “He is getting a second chance. If you don’t cherish the moments and the hard work you’re going to do, you need to quit.”

But Burns also adamantly points out that if he continues to work hard and progress, Taylor will win another world title.

Maybe by then, Taylor, once again, will be allowed to sit in the front row.

SAN ANTONIO — It was about 4 p.m. at a cavernous Alamodome that, in only a few hours, would hold 11,000 screaming boxing fans. But at this moment, in the middle of a Saturday afternoon in December with the sun still shining and the television cameras turned off, Jermain Taylor entered the ring for a bout for the first time in 14 months. If the approximately 200 fans who had filtered into the arena by that point recognized Taylor from his past, they did not act like it.

When Taylor knocked out the journeyman J. C. Candelo in the seventh round of their fight on Dec. 14 the buzz in the arena was nearly nonexistent. Taylor’s was the second fight on a big card, and his bout — a fight, mind you, that in Taylor involved a former undisputed middleweight champion who had twice beaten Bernard Hopkins — was not seen on television.

Taylor won the fight. He celebrated. He left the ring. And almost immediately afterward, the boxing world focused on something else.

This is where Taylor finds himself these days. This is what happens when a 35-year-old — who was knocked out twice in terrifying fashion by world-class super middleweights in a six-month stretch, who sustained a brain bleed that should have made him consider hanging up his boxing gloves forever — makes a comeback against long odds.

He is placed in the second row of the news conference dais, next to the boxers who are just beginning their careers and behind the big stars of the fight card. His quotations from that news conference are not distributed to the news media, because he is not fighting on TV. He becomes nearly as irrelevant as his competition, Candelo, the handpicked opponent that Taylor was fighting.

Why do it, then? Why subject yourself to more head blows, more punches to the face, the indignity of the back row? By all accounts, Taylor does not need the money. Why is he bothering?

“Man, what else am I supposed to do?” Taylor said a few minutes after dispatching Candelo.

A shrug of the shoulders.

“That’s what I’m saying,” he said. “I have nothing else to do. I’ve been doing this job since I was 12. This is my life. When I took those years off, I sat back and thought about it: ‘What am I supposed to do?’ ”

That was not the only question Taylor needed to answer as he began his journey back to relevancy. Taylor, a 2000 Olympic bronze medalist, also had to prove he was healthy enough to resume what had been an impressive career that included holding all four major middleweight belts at the same time.

But by 2009, he was coming off two losses to Kelly Pavlik — including one by knockout — and Taylor moved from the 160-pound middleweight class to the 168-pound super middleweight limit to challenge for Carl Froch’s world title. Although Taylor was ahead on two of the three judges’ scorecards, Froch knocked out Taylor with 14 seconds left in the 12th round. Six months later, Arthur Abraham brutalized Taylor in the final round with one punch that felled Taylor as if he had just stepped off a cliff. Only six seconds remained in that bout when it was stopped.

After the fight, Taylor asked his wife, Erica, and his promoter, Lou DiBella, in what round he had been stopped. He asked again a few minutes later. And again a few minutes after that. That was when Taylor’s team knew something was wrong, and soon after, Taylor, who had a brain bleed and a concussion, temporarily stepped away from the sport. His health, he knew, was at stake.

“I’ve seen a guy who I was with at the Olympics training camp, and he can’t even talk now,” Taylor said. “His brain swelled up, and his speech was slurred. I don’t want to be like that. But he chose his sport. I chose this sport. And I love it.”

It was in part for that reason that he wanted to return to boxing. That and because he does not want his children to see those brutal defeats mark the end of his career.

So he called his former trainer Pat Burns, who was fired during Taylor’s original middleweight title run, to see if they could work together again.

“No, no, no,” Burns said. Taylor flew to Miami to persuade him. Burns wanted Taylor to undergo neurological tests before he would commit to working with him. Taylor said he had been tested in his home state, Arkansas, but Burns still was not convinced the fighter was fit for a return.

Instead, Burns persuaded Taylor to visit the Mayo Clinic. He sent him to the Cleveland Clinic, and the stringent Nevada Athletic Commission. All three cleared Taylor to fight. “We’re ready to go, right?” Burns said an eager Taylor had asked him after the testing was complete. “Nope,” Burns said. “We’re going to take another six months off.”

Burns knows about bad concussions. A Marine, he sustained a head injury during a tour in Vietnam. As he recovered in a hospital for the next year, Burns saw the positive effects rest could have on a head injury. He made sure Taylor would have plenty of rest — 26 months of rest, in fact.

“The thing that’s important is he had two years off,” Burns said. “Unlike the N.F.L., where these guys get knocked out in the first quarter of the game, and if they’re coherent, they come back in the third quarter, the rest did Jermain good. Allow him to rest, he’ll be fine. If you continue to pound the bruised area, you’ll never recover. Whatever the damage was, he had more than enough time to heal.”

More than anything, Burns repeats the same mantra: it took us 24 fights, about four and a half years into Taylor’s career, to be good enough to beat Hopkins for the first time in 2005; It will take us some time now to get back to the championship level.

Taylor’s comeback attempt has not been smooth. He had three convincing wins from December 2011 to October 2012, but he was knocked down by Caleb Truax in a bout that mirrored the ending sequence of the Abraham fight. Taylor got up and won, but a confidence builder it was not.

In May 2012, a woman in Little Rock, Ark., accused Taylor of rape, and though she later recanted her story, the married Taylor admitted to ESPN.com this month that he had a relationship with the woman, whom he called a longtime friend.

But after 14 months out of the ring, his performance against Candelo was the best he has looked in his comeback. Until Taylor faces a truly dangerous opponent, however, nobody — not Taylor and certainly not Burns — knows how he will react.

“Very few boxers get a second chance,” Burns said. “He is getting a second chance. If you don’t cherish the moments and the hard work you’re going to do, you need to quit.”

But Burns also adamantly points out that if he continues to work hard and progress, Taylor will win another world title.

Maybe by then, Taylor, once again, will be allowed to sit in the front row.

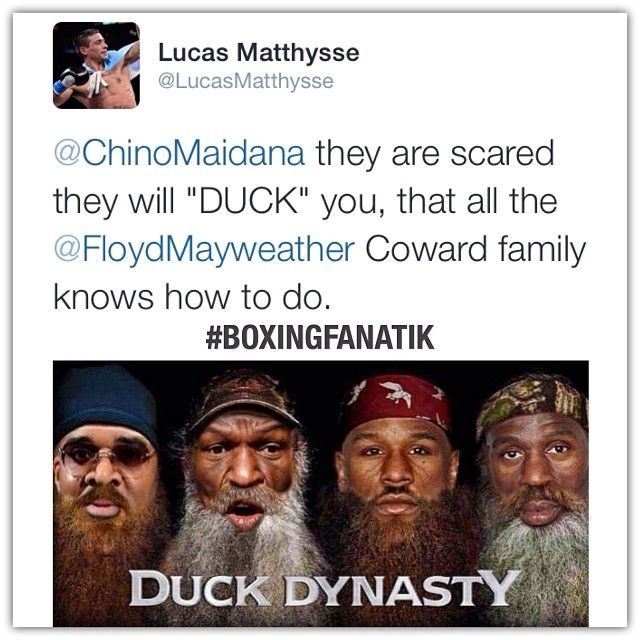

The Lucas twitter account is fake. I can't remember the real twitter account but he doesn't speak English let alone type it lol

Props:

CZAR and CZAR

BERMANE STIVERNE ON A MISSION TO BECOME 1ST HAITIAN-BORN HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION

By Press Release | January 02, 2014

On his mission to become the first Haitian-born heavyweight champion of the world, World Boxing Council (WBC) Silver champion Bermane "B. Ware" Stiverne (23-1, 20 KOs) still doesn't know exactly when and where he will be fighting for the vacant WBC heavyweight world title.

After patiently waiting 2 ½ years as the mandatory challenger, though, the 34-year-old Stiverne understands that he will be in his first world title fight sometime during the first-quarter of 2014 - date, place and network to be determined - in a rematch with Chris "The Nightmare" Arreola (36-3, 31 KOs).

Once Vitali Klitschko finally announced his retirement, the WBC mandated a title fight between its top two rated heavyweights, No. 1 Stiverne and No. 2 Arreola, ordering their respective promoters, Don King Productions and Goossen-Tutor Promotions, to begin negotiations. Stiverne-Arreola will go to a WBC purse bid in Mexico if an agreement is not reached by the January 17.

Stiverne knocked out Ray Austin on June 25, 2011 in the 10th round of their WBC heavyweight title eliminator to capture the WBC Silver championship. Last April in another WBC heavyweight title eliminator, Stiverne successfully defended his Silver belt, winning an impressive 12-round unanimous decision (118-109, 117-110, 117-10) over Arreola, breaking Arreola's nose and dropping him in the third round. Also, three purse bids for Stiverne to challenge Klitschko were postponed during Stiverne's arduous journey to his dream of fighting for the world title.

"I believe that good things happen to those who wait," Stiverne said sounding more like a philosopher than world heavyweight title challenger. "I also believe that one of my best qualities is to be patient for things that I want and care about in life, especially if I'm putting in work at 110-percent.

"I am not disappointed that I won't be fighting Klitschko. All I care about right now is to get my hands on that green belt and to be the first Haitian heavyweight champion of the world. I have the best team in boxing to take care of this matter. It is not my concern about where or when. My job is to be ready when the time and date comes."

"Although we've been patiently waiting," Stiverne's manager Camille Estephan (Eye Of The Tiger Management) noted, "we have not been sitting idle. Bermane has been hard at work, perfecting his skills and abilities, and his time waiting has been an investment. We will show that the sacrifice in efforts during that time has, without doubt, produced the best heavyweight in the world. Bermane is eager to show that in his upcoming performance."

Stiverne, who lives in Montreal and trains in Las Vegas, isn't looking at his fight with Arreola as a rematch. "As far as I'm concerned," Stiverne explained, "this will be the first time I fight him. My performance will be impeccable and very painful. I will knock his ass out!"

By Press Release | January 02, 2014

On his mission to become the first Haitian-born heavyweight champion of the world, World Boxing Council (WBC) Silver champion Bermane "B. Ware" Stiverne (23-1, 20 KOs) still doesn't know exactly when and where he will be fighting for the vacant WBC heavyweight world title.

After patiently waiting 2 ½ years as the mandatory challenger, though, the 34-year-old Stiverne understands that he will be in his first world title fight sometime during the first-quarter of 2014 - date, place and network to be determined - in a rematch with Chris "The Nightmare" Arreola (36-3, 31 KOs).

Once Vitali Klitschko finally announced his retirement, the WBC mandated a title fight between its top two rated heavyweights, No. 1 Stiverne and No. 2 Arreola, ordering their respective promoters, Don King Productions and Goossen-Tutor Promotions, to begin negotiations. Stiverne-Arreola will go to a WBC purse bid in Mexico if an agreement is not reached by the January 17.

Stiverne knocked out Ray Austin on June 25, 2011 in the 10th round of their WBC heavyweight title eliminator to capture the WBC Silver championship. Last April in another WBC heavyweight title eliminator, Stiverne successfully defended his Silver belt, winning an impressive 12-round unanimous decision (118-109, 117-110, 117-10) over Arreola, breaking Arreola's nose and dropping him in the third round. Also, three purse bids for Stiverne to challenge Klitschko were postponed during Stiverne's arduous journey to his dream of fighting for the world title.

"I believe that good things happen to those who wait," Stiverne said sounding more like a philosopher than world heavyweight title challenger. "I also believe that one of my best qualities is to be patient for things that I want and care about in life, especially if I'm putting in work at 110-percent.

"I am not disappointed that I won't be fighting Klitschko. All I care about right now is to get my hands on that green belt and to be the first Haitian heavyweight champion of the world. I have the best team in boxing to take care of this matter. It is not my concern about where or when. My job is to be ready when the time and date comes."

"Although we've been patiently waiting," Stiverne's manager Camille Estephan (Eye Of The Tiger Management) noted, "we have not been sitting idle. Bermane has been hard at work, perfecting his skills and abilities, and his time waiting has been an investment. We will show that the sacrifice in efforts during that time has, without doubt, produced the best heavyweight in the world. Bermane is eager to show that in his upcoming performance."

Stiverne, who lives in Montreal and trains in Las Vegas, isn't looking at his fight with Arreola as a rematch. "As far as I'm concerned," Stiverne explained, "this will be the first time I fight him. My performance will be impeccable and very painful. I will knock his ass out!"

AL BERNSTEIN NOT OPTIMISTIC ABOUT ADRIEN BRONER'S CHANCES AT 147 OR 140: "HE NEEDS TO GET HIMSELF BACK DOWN TO 135"

By Ben Thompson | January 02, 2014

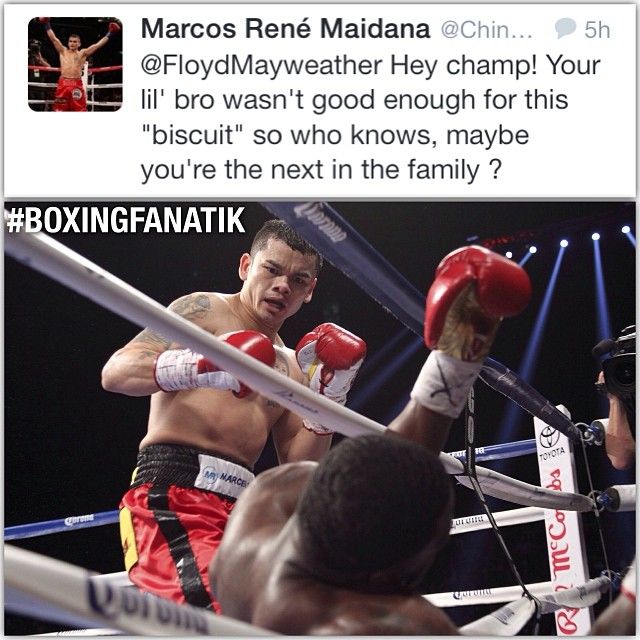

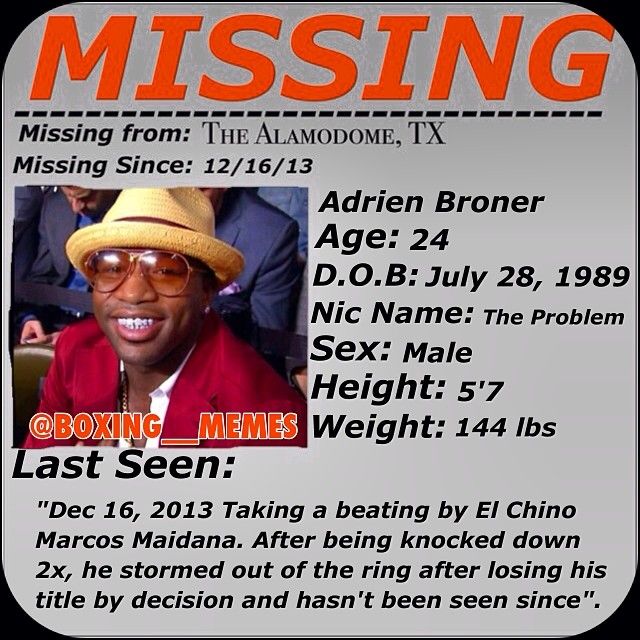

"Not to throw dirt on him, but that very night, you look at the difference between how Keith Thurman reacted to early adversity and how Adrien Broner did. Both of them got hit hard early. Thurman was able to shake it off, figure out a way past it, and win, and Broner wasn't," stated Showtime commentator Al Bernstein, who shared his thoughts on Adrien Broner's upset loss to Marcos Maidana and what the future may hold for the former welterweight champion. According to Bernstein, Broner can bounce back, but only if he realizes that he's not quite ready to compete with the naturally bigger fighters in both the welterweight and the jr. welterweight divisions.

"Now Broner is in an interesting situation because his problem...his big problem... one of his problems is I think he is fighting 2 weight classes too high at 147. At 135, he was able to beat those fighters with his power; even though he didn't throw a lot of punches, he was able to beat them with power. He was physically a little stronger than them. He could fight tall and not get hit with a lot of punches," Bernstein explained during a recent interview with FightHype's Percy Crawford. "But at either 140 or 147, in my opinion, he's gonna be facing monstrous punchers who are a little bit bigger and I think for Adrien Broner, it was absolutely essential if he wants to put his career back on track, he needs to get himself back down to 135. He only had a couple of fights at 135. He moved up from 130. He should be able to get to 135 because he's physically not that big, and see what he can do at that weight division. I'm not optimistic for Adrien Broner at 140 or 147."

By Ben Thompson | January 02, 2014

"Not to throw dirt on him, but that very night, you look at the difference between how Keith Thurman reacted to early adversity and how Adrien Broner did. Both of them got hit hard early. Thurman was able to shake it off, figure out a way past it, and win, and Broner wasn't," stated Showtime commentator Al Bernstein, who shared his thoughts on Adrien Broner's upset loss to Marcos Maidana and what the future may hold for the former welterweight champion. According to Bernstein, Broner can bounce back, but only if he realizes that he's not quite ready to compete with the naturally bigger fighters in both the welterweight and the jr. welterweight divisions.

"Now Broner is in an interesting situation because his problem...his big problem... one of his problems is I think he is fighting 2 weight classes too high at 147. At 135, he was able to beat those fighters with his power; even though he didn't throw a lot of punches, he was able to beat them with power. He was physically a little stronger than them. He could fight tall and not get hit with a lot of punches," Bernstein explained during a recent interview with FightHype's Percy Crawford. "But at either 140 or 147, in my opinion, he's gonna be facing monstrous punchers who are a little bit bigger and I think for Adrien Broner, it was absolutely essential if he wants to put his career back on track, he needs to get himself back down to 135. He only had a couple of fights at 135. He moved up from 130. He should be able to get to 135 because he's physically not that big, and see what he can do at that weight division. I'm not optimistic for Adrien Broner at 140 or 147."

AL BERNSTEIN TABS KEITH THURMAN AS A FUTURE OPPONENT FOR FLOYD MAYWEATHER

By Ben Thompson | January 01, 2014

"The one person that I think demonstrated to all of us that he is a force to be reckoned with and will be is Keith Thurman," stated Showtime commentator Al Bernstein, who shared his thoughts on undefeated WBA interim welterweight champion Keith Thurman and the breakout year he had in 2013. As far as Bernstein is concerned, Thurman's performances in his knockout victories over Diego Chaves and Jesus Soto Karass proved that he's much more than just a one-dimensional knockout artist. In fact, Bernstein believes that Thurman is just 1 or 2 fights away from being a legitimate opponent for undefeated pound-for-pound king Floyd "Money" Mayweather.

"Keith Thurman has done two things. He did the same thing in both of his fights against Chaves and the one against Jesus Soto Karass. He suffered adversity early. Against Chaves, he got hit with some big punches and realized he had to box a little bit. He did box and then got back to his power game and stopped Chaves. In the Jesus Soto Karass fight, if you remember, he was hit with a monstrous overhand right in the first round and it almost caught him cold. He rallied from that, kept his head about him, and rallied for a victory," Bernstein explained during a recent interview with FightHype's Percy Crawford. "Keith Thurman is the goods and I believe that in another fight or two, he is likely to be an opponent for Mayweather and if he gets a 38 year old Floyd Mayweather, I think it's gonna be a very fun fight to watch."

By Ben Thompson | January 01, 2014

"The one person that I think demonstrated to all of us that he is a force to be reckoned with and will be is Keith Thurman," stated Showtime commentator Al Bernstein, who shared his thoughts on undefeated WBA interim welterweight champion Keith Thurman and the breakout year he had in 2013. As far as Bernstein is concerned, Thurman's performances in his knockout victories over Diego Chaves and Jesus Soto Karass proved that he's much more than just a one-dimensional knockout artist. In fact, Bernstein believes that Thurman is just 1 or 2 fights away from being a legitimate opponent for undefeated pound-for-pound king Floyd "Money" Mayweather.

"Keith Thurman has done two things. He did the same thing in both of his fights against Chaves and the one against Jesus Soto Karass. He suffered adversity early. Against Chaves, he got hit with some big punches and realized he had to box a little bit. He did box and then got back to his power game and stopped Chaves. In the Jesus Soto Karass fight, if you remember, he was hit with a monstrous overhand right in the first round and it almost caught him cold. He rallied from that, kept his head about him, and rallied for a victory," Bernstein explained during a recent interview with FightHype's Percy Crawford. "Keith Thurman is the goods and I believe that in another fight or two, he is likely to be an opponent for Mayweather and if he gets a 38 year old Floyd Mayweather, I think it's gonna be a very fun fight to watch."

Sergio Martinez: Cotto May Not Even Last Five Rounds!

By Elisinio Castillo, notifight.com

WBC middleweight champion Sergio Martinez (51-2-2, 28KOs) will be looking for blood if a fight is finalized with Puerto Rican superstar Miguel Cotto (38-4, 31KOs) for June 7th at New York's Madison Square Garden.

The negotiations continue, with Martinez angered because he claims Cotto is making a high volume of demands. He says Cotto should remember that he is the challenger and not the champion in the equation.

"He should never forget that I'm the champion. He has a lot of demands, but I'm the champion. I'll say it, I don't think that he'll last five rounds. I would like to fight Cotto, but he is showing signs that he doesn't want to [fight], by asking for complicated conditions and he does not respect boxing history. I'm ready to knock Cotto out in five or six rounds and I know I will. He can not resist me. Disrespecting me is a very unfortunate thing. He should not forget that I'm the champion," Martinez said.

By Elisinio Castillo, notifight.com

WBC middleweight champion Sergio Martinez (51-2-2, 28KOs) will be looking for blood if a fight is finalized with Puerto Rican superstar Miguel Cotto (38-4, 31KOs) for June 7th at New York's Madison Square Garden.

The negotiations continue, with Martinez angered because he claims Cotto is making a high volume of demands. He says Cotto should remember that he is the challenger and not the champion in the equation.

"He should never forget that I'm the champion. He has a lot of demands, but I'm the champion. I'll say it, I don't think that he'll last five rounds. I would like to fight Cotto, but he is showing signs that he doesn't want to [fight], by asking for complicated conditions and he does not respect boxing history. I'm ready to knock Cotto out in five or six rounds and I know I will. He can not resist me. Disrespecting me is a very unfortunate thing. He should not forget that I'm the champion," Martinez said.

Stephen Espinoza, Head Of Showtime Boxing, Says Floyd Mayweather "will Fight Manny Pacquiao Anywhere, Any Time"

http://blogs.telegra...where-any-time/

Stephen Espinoza, Showtime Executive Vice President, has insisted that Floyd Mayweather "will fight Manny Pacquiao anywhere, any time" and hinted that if the Filipino parted with Bob Arum for one contest, the megafight would go ahead.

Espinoza told The Telegraph that there were clear hurdles to overcome, to make a reality the fight which boxing fans around the world have wanted for almost four years. “I know Floyd is not the issue,” Espinoza told me this weekend in Las Vegas. “Floyd wants the fight. Floyd will fight Manny Pacquiao anywhere, any time. Unfortunately, there is a promotional conflict which are the issue.

However, Amir Khan, said Espinoza, is a “leading contender” to challenge Mayweather Jnr on May 3, but the decision on the opponent is still “wide open”, insisted the head of Showtime Sports revealed on Sunday.

Mayweather will meet his televisual paymasters Showtime over the next week to narrow down the contenders. Espinoza confirmed on Sunday that the Argentine Marcos Maidana, and Khan, are “under consideration”. But it is understood they may not be the only two in a group of fighters that Mayweather is considering.

“

Khan is definitely one of the leading contenders for the fight,” Espinoza told The Telegraph. “I know Amir wants the fight. Floyd hasn’t made a decision. I expect an announcement by mid-January or the end of January.

“It is still wide open. Floyd has not made a decision yet about who he is going to fight on May 3. Obviously, Marcos Maidana is making a late case and a strong argument for the fight, but Amir is definitely there in the conversation.

http://blogs.telegra...where-any-time/

Stephen Espinoza, Showtime Executive Vice President, has insisted that Floyd Mayweather "will fight Manny Pacquiao anywhere, any time" and hinted that if the Filipino parted with Bob Arum for one contest, the megafight would go ahead.

Espinoza told The Telegraph that there were clear hurdles to overcome, to make a reality the fight which boxing fans around the world have wanted for almost four years. “I know Floyd is not the issue,” Espinoza told me this weekend in Las Vegas. “Floyd wants the fight. Floyd will fight Manny Pacquiao anywhere, any time. Unfortunately, there is a promotional conflict which are the issue.

However, Amir Khan, said Espinoza, is a “leading contender” to challenge Mayweather Jnr on May 3, but the decision on the opponent is still “wide open”, insisted the head of Showtime Sports revealed on Sunday.

Mayweather will meet his televisual paymasters Showtime over the next week to narrow down the contenders. Espinoza confirmed on Sunday that the Argentine Marcos Maidana, and Khan, are “under consideration”. But it is understood they may not be the only two in a group of fighters that Mayweather is considering.

“

Khan is definitely one of the leading contenders for the fight,” Espinoza told The Telegraph. “I know Amir wants the fight. Floyd hasn’t made a decision. I expect an announcement by mid-January or the end of January.

“It is still wide open. Floyd has not made a decision yet about who he is going to fight on May 3. Obviously, Marcos Maidana is making a late case and a strong argument for the fight, but Amir is definitely there in the conversation.

Props:

CZAR and CZAR

Richardson: Bradley, Garcia Capable Of Shocking Floyd

By Chris Robinson

As the days go by, we continue to wait for word on Floyd Mayweather’s next ring opponent.

At the moment there seems to be a very strong chance that Mayweather will end up facing off with British star Amir Khan on May 3 from the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

And while Khan surely serves as one of the biggest names for Mayweather at the moment, North Philadelphia’s Naazim Richardson has two other prizefighters in mind who could possibly trouble, and maybe even defeat Mayweather.

“Tim [Bradley] and Danny Garcia are capable of beating anybody in boxing,” The Zen-like trainer told me recently when discussing the WBO welterweight titlist and the WBA/WBC junior welterweight champion.

“Tim and Danny Garcia are young versions of a Bernard Hopkins,” Richardson added. “You can never gauge them. You can’t watch film on them. You can’t anticipate with them. Because they are super over-achievers. What Bernard Hopkins was. What Joe Frazier was.”

And while Richardson isn’t bold enough to side with either man against Mayweather, he wouldn’t be stunned if either pulled an upset.

“If Tim Bradley or Danny Garcia were to beat Floyd Mayweather I would not be shocked,” Richardson stated. “Would you bet against Floyd? F*** no. The only person you’re supposed to bet against Floyd with is Wladimir Klitschko on a good day.”

It’s obvious in speaking with Richardson just how much respect he has towards the Grand Rapids native, however.

“Floyd is one of them fighters now who you aren’t supposed to bet against until you see him lose,” Richardson explained. “He’s that special of a kid. But Tim or Danny getting past him would not shock me at all.”

By Chris Robinson

As the days go by, we continue to wait for word on Floyd Mayweather’s next ring opponent.

At the moment there seems to be a very strong chance that Mayweather will end up facing off with British star Amir Khan on May 3 from the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

And while Khan surely serves as one of the biggest names for Mayweather at the moment, North Philadelphia’s Naazim Richardson has two other prizefighters in mind who could possibly trouble, and maybe even defeat Mayweather.

“Tim [Bradley] and Danny Garcia are capable of beating anybody in boxing,” The Zen-like trainer told me recently when discussing the WBO welterweight titlist and the WBA/WBC junior welterweight champion.

“Tim and Danny Garcia are young versions of a Bernard Hopkins,” Richardson added. “You can never gauge them. You can’t watch film on them. You can’t anticipate with them. Because they are super over-achievers. What Bernard Hopkins was. What Joe Frazier was.”

And while Richardson isn’t bold enough to side with either man against Mayweather, he wouldn’t be stunned if either pulled an upset.

“If Tim Bradley or Danny Garcia were to beat Floyd Mayweather I would not be shocked,” Richardson stated. “Would you bet against Floyd? F*** no. The only person you’re supposed to bet against Floyd with is Wladimir Klitschko on a good day.”

It’s obvious in speaking with Richardson just how much respect he has towards the Grand Rapids native, however.

“Floyd is one of them fighters now who you aren’t supposed to bet against until you see him lose,” Richardson explained. “He’s that special of a kid. But Tim or Danny getting past him would not shock me at all.”