Scientists in China revealed that they found a giant bird whose fossilized bones measure 8 meters (26 feet) in length, 5 meters (16 feet) tall and which weighed 1,400 kilograms (3,000 pounds) and lived 85 million years ago. The fossil was uncovered in the Erlian Basin of northern China's Inner Mongolia, said Xu Xing, a paleontologist at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology & Paleoanthropology in Beijing who co-authored a paper about the find that was published in the journal Nature. This feathered but flightless specimen challenges the prevailing hypothesis about the evolution of birds.

Remarkably, the find was made in April 2005 in front of a Japanese TV crew who were interviewing the Chinese scientists about three earlier fossil finds in the Erlian Basin on the Mongolian-Chinese border. Initially, the scientists chose a random site to demonstrate to the cameras how one of their previous fossils had been discovered. But as they dug, they unexpectedly found a bone that they thought was an example of a Tyrannosaur -- at first. But upon a closer look under the intense light of a TV camera, they realized they were looking upon something new to science: the remains of a gigantic, surprisingly bird-like dinosaur.

"[This is] the biggest toothless dinosaur ever found because some dinosaurs have both a small beak and many teeth," observed Xu.

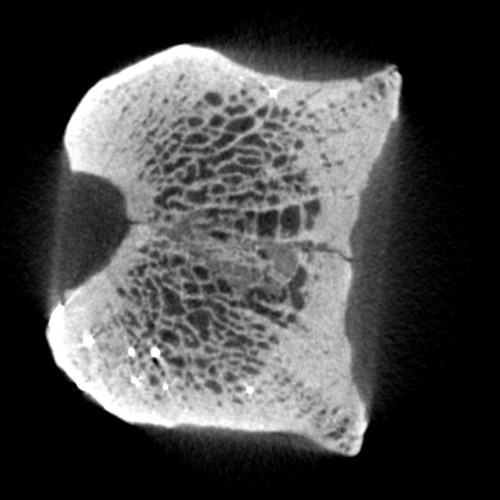

Further examination under the camera lights revealed that the fossil had an unusual spongy lightweight tail and arm bones that are typical of birds and bird-like dinosaurs (see below). Based on the growth rings seen in the fossilized bones (below), the scientists estimated that this specimen was an 11 year old animal that might possibly have lived to around the age of 18 -- so there could have been even larger versions of this bird running around. The animal was formally described as a new genus and species, Gigantoraptor erlianensis.

Micro-structure of Gigantoraptor bone showing the annual growth lines (arrows).

Even though it looks like a bird, Gigantoraptor's height is comparable to the formidable carnivore, Tyrannosaurus rex. No one is quite sure yet if Gigantoraptor was an herbivore, which typically have small heads and long necks, or a carnivore, which have sharp claws, because this dinosaur has both, Xu explained.

Further, unlike T. rex, this animal had a formidable ten inch beak and slender legs, and apparently also had feathers. Thus, this species was 35 times larger than its closest relatives, the feathered Caudiperyx and Protarchaeopteryx, which are small, feathered dinosaurs.

"We think it's the largest feathered animal ever to have been discovered," remarked Xu.

Previously, the largest known feathered animal was the 500-kilogram Stirton's Thunder Bird, Dromornis stirtoni, which lived in Australia 8-6 million years ago and was one-third the size of Gigantoraptor.

Because of its large size, this fossil is challenging the prevailing scientific hypothesis that dinosaurs became smaller as they evolved into birds while larger dinosaurs retained less birdlike characteristics.

"This is like having mouse that is the size of a horse or cow," explained Xu. "It is very important information for us in our efforts to trace the evolution process of dinosaurs to birds. It's more complicated than we imagined."

Curiously, even though Gigantoraptor stands twice the height of a man at its shoulder, its limbs remained gracile rather than becoming shorter and heavier.

"Normally, when dinosaurs become large in size, they have proportionally stouter limbs and shorter lower legs than their small-sized relatives," Xu observed. "However, Gigantoraptor has much more slender limbs and longer lower legs than similarly-sized theropods."

Caudiperyx, Protarchaeopteryx and Gigantoraptor all belong to a group of bird-like dinosaurs known as oviraptors, which were previously known to be human-sized or smaller.

"It's one of the last groups of dinosaurs that we would expect to be that big," remarked Mark Norell, curator of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

But other paleontologists disagree, saying that Gigantoraptor would be a natural step in the evolutionary process of the oviraptors.

"Almost every group that has evolved has tended to evolve giant forms," observed Philip Currie, a paleontologist at the University of Alberta, Canada.

The typical evolutionary pattern shows that animals tend to become bigger over time because large body size means they have an easier time obtaining food, impressing potential mates and deterring predators. Large size is a disadvantage as well; representing evolutionary trade-offs because bigger animals require more food, larger territories, they produce fewer offspring and they reproduce less often than do smaller animals. As a result, they are more vulnerable to evironmental disturbances, as was the case when the dinosaurs -- and Gigantoraptor -- went extinct approximately 65 million years ago.

"It was an unexpected finding," said Xu of the serendipitous discovery.

The bones were discovered near the city of Erenhot on the Chinese-Mongolian border. Erenhot, which is known for its many fossils, refers to itself as "dinosaur town." This city will spend more than 100 million yuan ($13.11 million) on a new dinosaur fossil museum this year to attract tourists.

A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China by Xing Xu, Qingwei Tan, Jianmin Wang, Xijin Zhao & Lin Tan Nature Vol 447(14 June 2007):844-847 [doi:10.1038/nature05849